Born in 1939 in Denver (US). Lives and works in New York (US)

1979

Brochure

Year of Purchase: 2014

“[…] after the revolution, who is going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?”: this eloquent question is the cornerstone of Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s declaration of intent in Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969! Written in 1969, against the background of feminist movements in the United States, which challenged women’s position in society and had a major impact on the world of art, this manifesto is a springboard to the artist’s whole practice, which encompasses ecological awareness, feminism, and cultural representations of labor. Mierle Laderman Ukeles uses her work to challenge value hierarchies that oppose development and innovation to maintenance and sustainability, where in reality these two sets of notions are complementary. A personal event was the catalyst of her manifesto: the birth of her first child. She found herself faced with a division of her person between artist and mother, and felt the tension between creative freedom and repetitive household chores. As a result, she became aware of the necessity of domestic tasks in order to ensure the wellbeing of her family as well as of the lack of consideration they elicited. She chose to be an artist since, according to her, the figure of the artist embodies freedom: why shouldn’t she use her artistic freedom to define what constitutes art? She thus declared that maintenance work was a creative act.

Her manifesto attracted the attention of the art critic and artist Lucy R. Lippard. Laderman Ukeles also submitted a proposal for an exhibition “CARE,” which she would develop in a series of performances. Among others, she proposed to perform the tasks necessary for the functioning of the exhibition space as if it were her own home: scrub the floor, change light bulbs … The artist thus spotlighted the activities involved in museum maintenance that are normally hidden from the public, thereby also underscoring the relationship between feminine domestic work and maintenance labor performed by workers in public space. In 1976, Mierle Laderman Ukeles staged the performance I Make Maintenance Art One Hour Every Day as part of an exhibition at the Whitney Museum in New York. She invited the 300 maintenance workers employed at the museum annex to spend one hour of their workday thinking about their professional activity as art. Speaking of the performance, David Bourdon suggested ironically that the NYC Department of Sanitation should apply for the National Endowment for the Arts to make up for the budgetary cuts. Mierle Laderman Ukeles took his suggestion literally: in 1977 she became the first and only artist-in-residence at the Department of Sanitation.

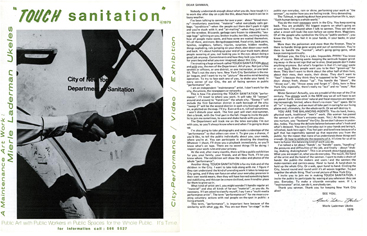

Touch Sanitation (1977–1980), which comprises two projects, is the first work resulting from this collaboration. In Handshake Rituals, Mierle Laderman Ukeles shook hands with every one of over 8,500 sanitation workers in New York. With every handshake—a powerful social gesture that symbolizes our connection to others and mutual dependence foregrounded in the artist’s second manifesto, Sanitation Manifesto! (1984)—the artist expressed her gratitude for the job done by the city workers and thanked each of them for keeping New York alive. Mierle Laderman Ukeles has adopted an essentially human approach that does not view sanitation workers as an anonymous mass. She valorizes their work, largely disparaged even while it is paradoxically indispensable to the overall balance of the city. The second part of Touch Sanitation is called Follow in Your Footsteps. Here, the artist reproduced the gestures of the sanitation workers whom she followed on their daily routine. The work, for the most documented with photographs, had necessitated scrupulous coordination to meet with every employee to whom the artist had sent an introductory letter outlining the project. As an extension of the project, the artist made two installations to accompany the exhibition The Touch Sanitation Show (1984) at the Ronald Feldman Gallery. The installations emphasize the working conditions of the sanitation workers (Sanman’s Place_) and the complex nature of their work (_Maintenance City). In parallel to two other works done in the United States and abroad, the artist has continued to initiate artistic projects with the Department of Sanitation. Flow City (1983-1995), for example, foregrouned the operation of a waste management transfer station.

Émilie Blanc