Born in 1945 in Barranquilla (CO). Lives and works in Barranquilla (CO)

1971-2004

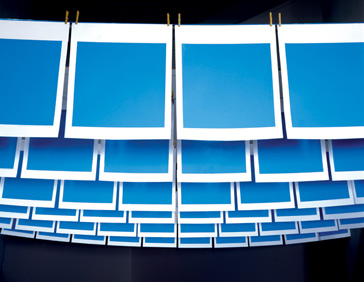

Installation

Dimension variable

Year of Purchase: 2011

In 1971, a Young Colombian, Álvaro Barrios, was working on El Mar Caribe (The Caribbean Sea) for the 7th Biennale in Paris.1 The circumstance is far from insignificant: even though the event had aspired to being international since its launch in 1959, it struggled to integrate areas outside the ambit of cosmopolitan lifestyle. As a further evidence of that inability, the seventh installment of the biennale, with its thematic triad of Concept, Intervention, and Hyperrealism, risked creating in extremis a catch-all category. Despite being clearly conceptual and minimal in nature, El Mar Caribe was simply triaged by nationality and classified under Option IV. The initial project would have brought together “a giant map of Colombia, its national emblem, and its flag.”2 Perhaps the idea was to offer the very Western Biennale a little lesson in geography.

However, assertions of identity are not part of Barrrios’s vocabulary which, on the contrary, assimilates commonplaces of Western art into delightful drawings, collages, and cartoons, replete with impure and anachronic conjunctions: art nouveau, symbolism, surrealism, pop art, and science fiction. Erudite irreverence, poor taste, and pastiche are in the spirit of dandyism. As one of the variants of the project attests,3 viewers were initially meant to write personal comments about Columbia on the map fragments or burn holes with a cigarette, while a voice would spout from a speaker all kinds of tourist information about the country, down to the prices of flights. The project Columbia finally became El mar Caribe, swapping Columbia for the Caribbean Sea, blotting out the readability of the land with solid blue: an impenetrable cerulean blue of perfectly amnesic exoticism.

The 125 silkscreens of El Mar Caribe, imprinted recto-verso with an expanse of pure cyan, with geodesic coordinates in the footer, are enlargements of the square sections of a marine map. The cartographic fiction has been defeated: the spatial environment breaks up the integrity, the flatness, and the frontality which turned the planisphere into an intelligible image. The cartographer’s aggressive and authoritative grid is burst into pieces on the ceiling. The prints are suspended on strings and held by clothes clips as in some gigantic laundry room where one would wait for all the water to finally evaporate. Of course, the installation also evokes a popular form of communication close to the artist’s heart: that of “clothesline literature,” periodicos de cordel, or illustrated magazines hung on cords in the street, intended for uneducated readership. Unexpectedly, the installation succeeds at blending opposing registers, and plants these vernacular borrowings at the very heart of untouchable minimalism.

Hélène Meisel

1 The Paris Biennale existed from 1959 to 1985.

2 Septième Biennale de Paris [Paris, Parc floral de Vincennes, Sept. 24 – Nov. 1, 1971]. Paris, 1971 (Exhibition catalog), p. 224

3 Details described in Hacia Perfil del Arte Latinamericano (Towards a Profile of Latin American Art), 1972, curated by Jorge Glusberg, CAYC (Center for Art and Communication), Buenos Aires.