Born in 1920 in Buenos Aires (AR). Died in 2013 in Buenos Aires (AR)

1980

Ink, paper

98 x 98,8 cm

Year of Purchase: 2008

Although it intersects different artistic currents which have shaped the last few decades, the work of the Argentinean artist León Ferrari has stayed remarkably free and eluded classification. Employing a fusion of ideas and esthetics, Ferrari tackles conceptual art without giving up form, the political – without giving up the poetic, and the allegorical – without giving up the material. Showing a predilection for media that resist auratization and fetishization of a unique object, his work borrows from mail art and has taken advantage of photocopy, videotext, publishing, and journal articles.

It is precisely the use of these simple, reproducible modes of expression and graphically potent, uncomplicated images that Ferrari’s work owes its discreet subversiveness, and attempts at censoring it have only confirmed this. In 2004, a 1965 sculpture representing Christ crucified on a scale model of an American bomber was banned. The piece was strangely premonitory in the light of recent events, when the designation of an “axis of evil” helped rekindle a new form of religious war. Clear proof of art’s ability to remain current…

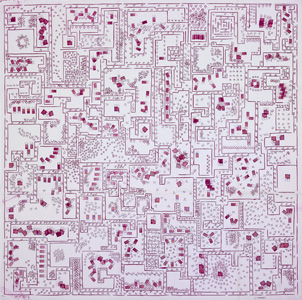

Fleeing the military dictatorship in his native country in 1976, the artist took refuge in Sao Paulo, Brazil. It was there that he made his first “heliographies.” These multiples on paper use architectural modeling to represent deliberately unreal city plans and fake, proliferating, and at times absurd architectonic structures. Other times, the lines render, at a more basic level, patterns of mass behavior. Beneath their playful and mesmerizing surface, Ferrari’s works are metaphors for an over-organized, over-determined world, unmasking the highly structured and potentially oppressive and aporetic character of modern city planning. The streams of cars or people symbolize the reification of city dwellers transformed into robots or urban furniture. Surface graphic functionalism turns into ornament. One could go further and discern in these representations, modeled on uniformization and organization, a metaphorical relation to a military order. City planning, cartography, scale models, and more generally a bird’s-eye view of the world, were developed for strategic, military, and war purposes. A generalized policy of gaze and knowledge in the service of the logic of domination and conquest. The carte d’état major (lit. military staff map) which is in use to this day, is one of the vestiges of that logic. Consequently, this organized, yet arbitrary vision evokes a sort of functional authoritarianism characteristic of military regimes which, as one can easily imagine, had a great impact on the artist. However, besides being politically engaged, the heliographies also function as mental architectures representing, through the motif of the labyrinth, psychic meanders, dead-ends, and short-cuts. Depending on the distance of the gaze, the entomologizing sociological vision appears either abstract or figurative, reassuring or dizzying, uniform or chaotic. Although produced in the 1970s, the heliographies are, once again, surprisingly current in that they offer the image and the experience of a contemporary world apprehended as vertigo, chaos, incomprehension, and meaningless order.

Guillaume Désanges